Knoedler Gallery’s scandal becomes a Netflix documentary

“Art is not what you see, but what you make others see ”

E. Degas

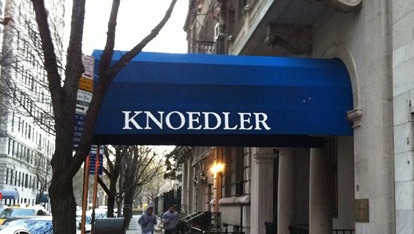

It was 2011, when one of New York’s historic art galleries in the heart of Manhattan, the Knoedler Gallery, closed its doors.

Those which were – officially – business reasons actually covered one of the most famous fake scandals in the art world for which Knoedler would soon make headlines.

Entrance of Knoedler Gallery in New York, Manhattan – Courtesy of Atribune

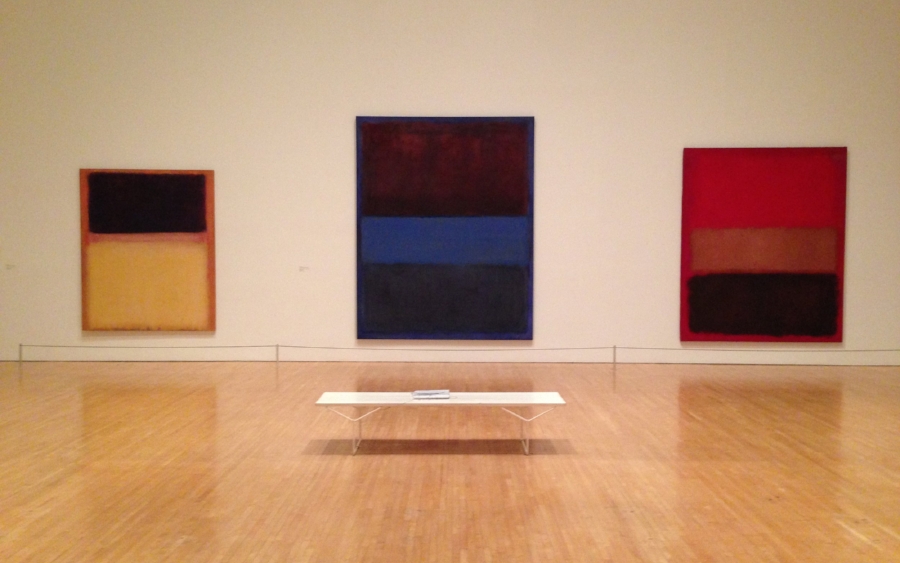

It seemed that the gallery, at the time managed by Anne Freedman, between 1994 and 2011 had sold to well-known collectors, with stratospheric prices, a series of artworks by the greatest artists of the twentieth century – Pollock, Rothko, Motherwell, de Kooning – which all turned out to be fake.

The alleged masterpieces had been brought to Knoedler by a certain Glafira Rosales, a presumed art dealer at the time, who together with her then-boyfriend Carlos Bergantinõs Diaz, cleverly illegally sold the paintings pretending them coming from private Swiss and Spanish collections (these fakes too, predictable ). Legend even has it that the woman transported the artworks to the Manhattan gallery in the trunk of her car.

Anne Freedman, Courtesy of the New York Times

The fraud set up by Rosales, before being exposed thanks to the fooled collectors – above all, the De Sole spouses – and an investigation by the FBI, generated a turnover of 80 million, of which 33 were collected directly by her.

In 2020 Barry Avrich, a Canadian director, turned this story into a documentary entitled Made you look: a true story about fake art, finally available on Netflix after various delays due to Covid.

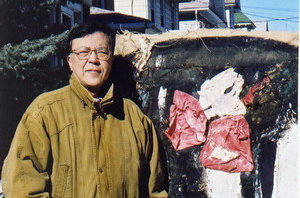

Avrich deserves great credit for being able to convince the main protagonists of the scandal to appear in the documentary. After the initial resistance, completely understandable, they realized how it could be an opportunity to explain their version of events and recover a minimum of that reputation which, in any case, had gone definitively lost. The documentary explains how the fakes, also exhibited in the largest museums in the world, were made by a Chinese man – also an artist – named Pei – Shen Qian whose skills as a forger, given the results, are surprising.

Pei-Shen Qian – Courtesy of Art History News

At the time of the scandal Qian, continuing to declare himself innocent and unaware of the facts, to escape the sentence returned to China, where he still lives – outside Shanghai – and where he continues to paint but without selling his works. On the opposite, the investigators were more than certain of his conscious involvement in the fraud. The mechanism was simple, Qian made the fakes and then it was Bergantinõs Diaz’s job to “age” the canvases with original methods: he used tea bags, the contents of the vacuum cleaner or the hot air of a hairdryer to simulate the natural decay or dirt due to time. And if this isn’t cinema.

Anne Freedman, on her side, has always defended herself by claiming that she was Rosales’ first victim and, after ten lawsuits – nine of which were settled and only one brought to trial – she even opened her own gallery in New York, the Freedman Art, where she continues to sell art to the few who still trust her. Meanwhile, Carlos Bergantinõs Diaz has returned to Spain to avoid sentencing and Glafira Rosales, after serving a relatively short sentence thanks to her lawyers, has found a job as a waitress in a diner.

Glafira Rosales with her lawyers – Courtesy di Artnet News

A surreal story that, in our opinion, finds its correct conclusion in one as disconcerting as – at this point – true quote by Thomas Hoving, director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art who, in 1977, stated:

“In my fifteen years at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, I have examined fifty thousand works of art of all kinds: a good 40% were either fake or so badly restored or badly attributed that they had to be considered fake” .