A perfect love: Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera

It is a love between two people, but at the same time between two artists. And in this particular case, it becomes impossible to separate a personal relationship from artistic production.

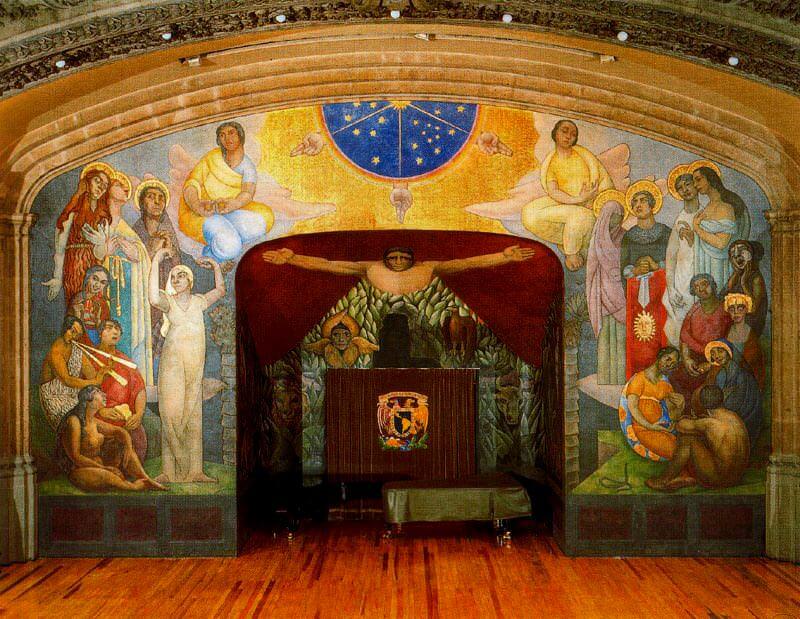

Diego Rivera, “La creación”, 1922, Anfiteatro Simón Bolívar Courtesy of www.diegorivera.org

Like all classic love stories, also this one begins with a chance encounter: it’s 1922, Frida Kahlo is 15 years old, she aspires to become a doctor and for this reason she attends the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, where a mural had been commissioned to Diego Rivera. At that moment their paths divide, and in the meantime Frida is the victim of a serious car accident that forces her to bed for a long time: in this moment her obsession with painting arises, as an escape that expresses an intrinsic need. And it is precisely at the end of this period of convalescence that the two meet again: Frida decides to show to Diego, already established artist, her artworks to have an opinion about them and he will let her enter the lively cultural (but also political) Mexican context. Thus begins an artistic partnership which becomes marriage in 1929, and again in 1940: Frida knows very well that it is not a choice in the name of serenity, but rather of recklessness because she is faced with a libertine spirit (“Why do I call him my Diego? He never was and never will be mine. He belongs to himself”). These are years of mutual adulteries, combined with the dramatic impossibility of having children due to her health conditions. She personally will admit, “I have suffered two serious accidents in my life, the first was when a tram hit me, the second was Diego.” This obviously difficult, almost sick relationship, is however animated by a profound feeling that becomes a driving force, but also a subject, for the art of both.

Frida Kahlo, Frida e Diego Rivera, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Courtesy of www.fridakahlo.org

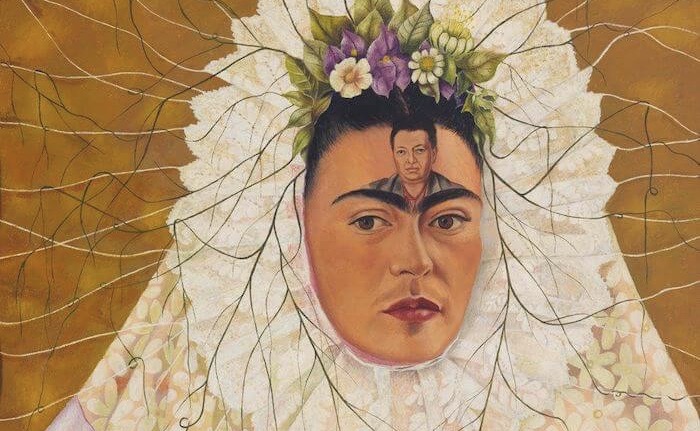

There are many self-portraits that Frida makes of herself, since she was immobilized in bed after her accident. Over the years, her love for Diego is also expressed in including him in these portraits: in “Frida and Diego Rivera” (1931, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art), Diego evidently appears much more ms than her, both physically than artistically. In fact, he holds a palette and brushes in his hand, while she represents herself in a subordinate position, as his partner, who holds his hand with her head that refers to him. In “Diego on my mind” (1943, Gelman Collection), Frida wears traditional clothes to demonstrate her Mexican essence and Diego appears in the center of her forehead, but it is not clear whether he represents a burden or a constant inspiration. Her works also express the pain felt so many times due to betrayals, moments of separation (“Las Dos Fridas” represents the split between the two identities of Frida, whose hearts are however connected: the first dressed in a white dress European style stained with blood, the second with the Mexican clothes so loved by Diego) and the missing children (“Henry Ford Hospital”: Frida is a small bloody figure in a huge bed; several elements are tied to her with a red thread, recalling precisely the lost son, his health problems, Diego himself).

Frida Kahlo, “Las dos Fridas”, 1939, Museo de Arte Moderno (Ciudad de Mexico) Courtesy of www.fridakahlo.org

Less frequently, but also Rivera portrays his partner revealing her strength and delicacy together as in “Desnudo sentado con brazos levantados”, showing her as a deity in “Portrait of Frida Kahlo”. Frida has never hidden the power and influence that the love for Diego had on her, and also the suffering that this relationship caused her continually but which was her lifeblood: “all the anger from which I passed, they only served to make me finally understand that I love you more than my own skin and that, even if you don’t love me in the same way, you still love me somehow “. But the sentiment was fully reciprocated by Diego, who however, perhaps only at the moment of the definitive loss of Frida, was he able to truly express it: “July 13, 1954 was the most tragic day of my life. I had lost my Frida, whom I would have loved forever. Only later did I realize that the best part of my life had been my love for Frida. “